New research suggests that early civilizations used mathematical techniques to mark property lines long before Greek scholars formalized such concepts. A recently analyzed clay tablet, crafted between 1900 and 1600 B.C.E. in Babylon, provides the earliest known evidence of applied geometry.

This artifact, known as Si.427, offers a glimpse into how land boundaries were determined in the Old Babylonian period. It has been revealed that geometric principles were utilized for practical purposes rather than purely theoretical exploration. As noted by mathematician Daniel Mansfield of the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Australia, this particular tablet contains legal and mathematical details about a field that had been partially sold, requiring its division.

Pythagorean triples—number sets that form right-angled triangles—are inscribed on the tablet, suggesting that these mathematical concepts were in use more than a thousand years before Pythagoras was born in 570 B.C. While the Greeks later developed trigonometry for astronomical studies, the Babylonians independently devised their own version, which was primarily applied to land measurement and boundary demarcation.

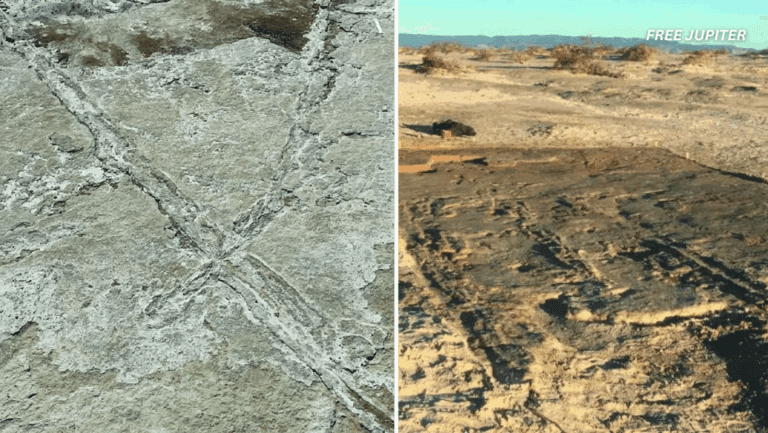

One side of Si.427 displays a diagram of rectangular fields, carefully proportioned with opposite sides of equal length. The reverse side contains a cuneiform inscription detailing the features of the land, including marshes, a threshing floor, and a nearby tower. Such meticulous documentation underscores the importance placed on accurate land division.

In the modern era, surveyors rely on GPS technology to establish precise property boundaries. During the Babylonian era, however, officials achieved similar accuracy using Pythagorean triples. The evidence suggests that surveyors employed these calculations to ensure fairness in land distribution and ownership disputes.

Previously, Mansfield and his colleague Norman Wildberger discovered that another Babylonian tablet, Plimpton 322, contained a list of Pythagorean triples. Their 2017 study, published in Discover magazine, suggested that the Babylonians utilized a base-60 numerical system to compute right-angled triangles. However, the exact purpose of these calculations remained unclear at the time.

A breakthrough came with the rediscovery of Si.427, which had been stored in the Istanbul Archaeology Museums since its excavation in 1894. Upon closer examination, it became apparent that this tablet provided a practical application of geometric principles—land surveying. This insight aligns with a period in history when landownership became increasingly privatized, necessitating precise boundary demarcations to prevent disputes.

Additional cuneiform tablets from the same era provide further context for how land conflicts were managed. One notable case mentions a legal dispute involving a landowner named Sin-bel-apli and a wealthy woman. The disagreement centered around valuable date palms located at the border of their properties. Official records describe how a local administrator dispatched a surveyor to resolve the matter, highlighting the crucial role of accurate measurements in maintaining peace among landowners.

Related Studies and Findings

Further research into Babylonian mathematics has unveiled several other examples of advanced mathematical practices. The Babylonians are credited with the earliest recorded use of algebraic techniques, as seen in tablets containing quadratic equations. Their numerical system, based on base-60, influenced modern timekeeping and angular measurement.

Another significant artifact, the YBC 7289 tablet, demonstrates that Babylonians had an understanding of square roots and could compute approximations of irrational numbers. This tablet contains a highly accurate approximation of the square root of 2, showcasing their advanced numerical capabilities centuries before Greek mathematicians formalized such concepts.

In addition, the Babylonians developed extensive multiplication tables and tables for solving linear and quadratic equations. These findings, derived from various clay tablets, illustrate a well-structured mathematical tradition. The use of a place-value notation system and their base-60 numbering allowed them to perform complex calculations with surprising efficiency, leading to advancements in astronomy and commerce.

Babylonian mathematics has been compared with the mathematical traditions of other ancient civilizations. Egyptian rope stretchers, for example, used knotted ropes to create right-angled triangles for land measurement, a practice closely resembling the use of Pythagorean triples. The Chinese Zhoubi Suanjing, an ancient mathematical text, also contains methods for calculating right triangles, indicating parallel developments in mathematical thought across different cultures.

Moreover, studies of Mesopotamian mathematical tablets suggest that Babylonian scholars understood mathematical sequences and geometric progressions. Evidence from cuneiform texts implies that they were capable of predicting celestial events based on mathematical models, further demonstrating the depth of their mathematical knowledge.

Research from historians and archaeologists continues to reveal new aspects of Babylonian mathematical achievements. Scholars have analyzed tablets related to economic transactions, taxation, and trade, which showcase advanced accounting techniques that relied on precise calculations. These findings reinforce the notion that mathematics was deeply embedded in administrative and economic activities as well as land surveying.

Influence on Modern Surveying and Geometry

The principles discovered in Babylonian tablets have had a lasting impact on mathematics and land surveying. The concept of using mathematical calculations for practical applications paved the way for modern surveying tools and techniques. The groma, an instrument believed to have originated in Mesopotamia, allowed ancient surveyors to measure straight lines and right angles with remarkable precision. This tool was later adopted and refined by Roman engineers, influencing the development of modern surveying equipment.

The Babylonian emphasis on accuracy in land measurement is reflected in contemporary legal frameworks for property boundaries. Modern cadastral surveys, which define property lines for ownership and taxation, share fundamental principles with the techniques documented in Si.427. The use of mathematical formulas to determine land areas, resolve disputes, and ensure fair distribution of property remains a crucial aspect of land management today.

Conclusion

The findings surrounding Si.427 and other Babylonian mathematical tablets reshape our understanding of early mathematics and its applications. While Greek scholars such as Pythagoras are often credited with pioneering geometry, evidence now suggests that practical geometric calculations had already been in use for more than a millennium in ancient Mesopotamia. These discoveries not only reveal the advanced knowledge possessed by the Babylonians but also demonstrate how mathematics was deeply integrated into daily life, long before it was studied as an abstract discipline.

As more artifacts are analyzed, further insights into the mathematical prowess of ancient civilizations are likely to emerge. The legacy of Babylonian applied geometry remains a testament to the ingenuity of early societies, whose techniques continue to influence modern mathematical principles. By examining these ancient methodologies, researchers gain a greater appreciation for the interconnected development of mathematical knowledge across human history.