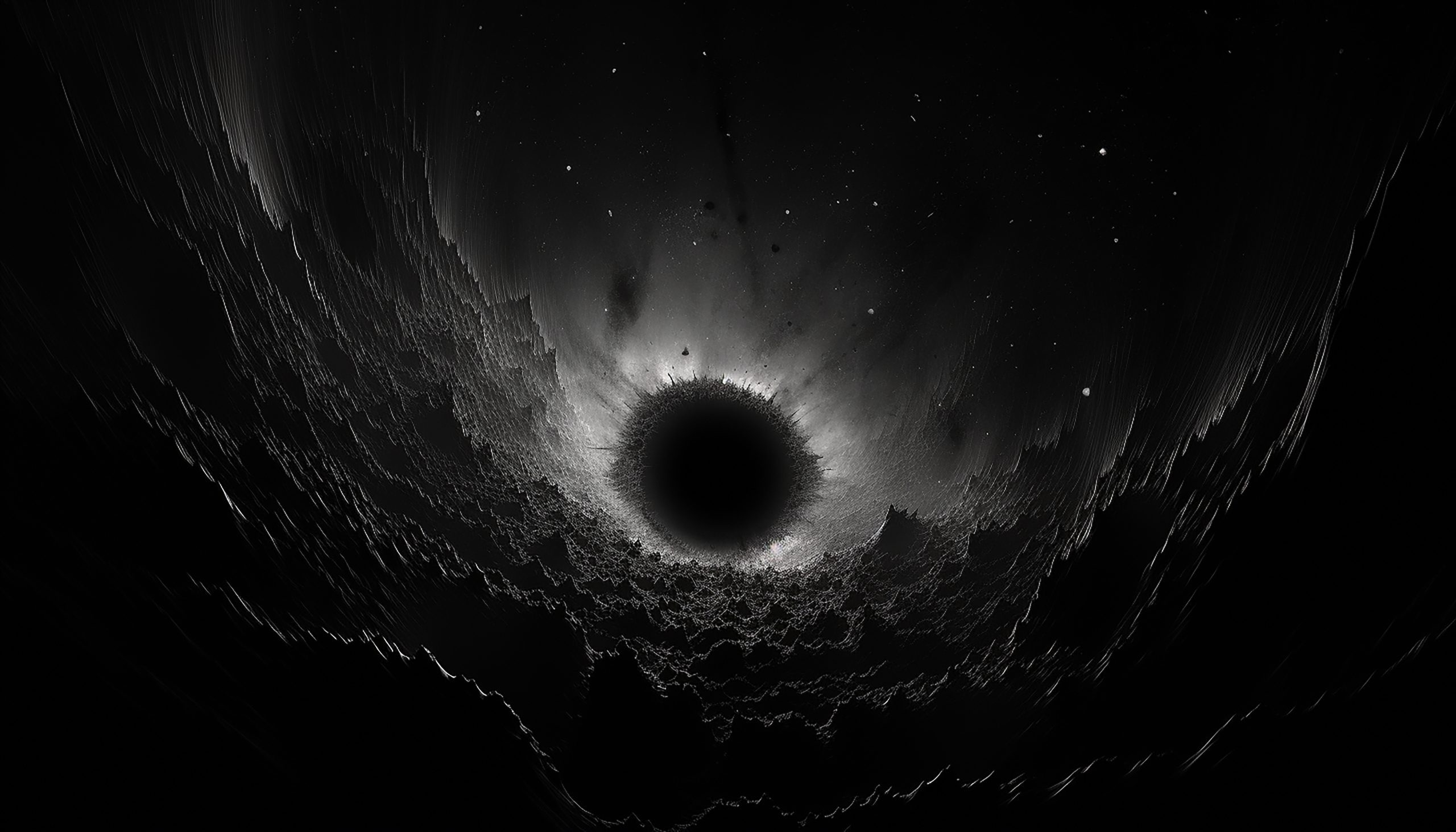

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) may have detected an extraordinary type of star for the first time—one that has long been theorized but never observed. These enigmatic objects, known as dark stars, are believed to be powered not by nuclear fusion, like ordinary stars, but by the self-annihilation of dark matter. Dark matter, an invisible substance thought to comprise approximately 85 percent of the universe’s mass, could provide the energy that fuels these mysterious stars. While more evidence is needed to confirm the nature of these newly identified objects, their discovery could significantly alter our understanding of how the first stars in the universe formed.

Bright Yet Mysterious

Despite their name, dark stars may have shone with incredible brightness—potentially a billion times more luminous than the sun. They could have reached masses up to a million times greater than that of our sun. Although these objects have never been definitively observed, theoretical models suggest they may have emerged shortly after the big bang. It is believed that they could have formed from massive clouds of hydrogen and helium collapsing within protogalaxies enriched with dark matter.

Possible Evidence from JWST

In a recent study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA, researchers reported that at least three distant objects observed by JWST—which had been previously classified as galaxies—might actually be individual dark stars. Katherine Freese, an astrophysicist at the University of Texas at Austin and co-author of the study, emphasized the significance of such a discovery, noting that the identification of a new type of star would be groundbreaking.

Still Awaiting Confirmation

The true nature of these objects has yet to be conclusively determined. Their properties align with characteristics expected from either dark stars or galaxies containing conventional, fusion-powered stars. However, according to study co-author Cosmin Ilie of Colgate University, JWST possesses the capability to differentiate between these possibilities. Given sufficient observational time, researchers hope to confirm the existence of dark stars within the telescope’s operational lifespan.

How Were the First Stars Formed?

The formation of the universe’s first stars has long been debated. Traditionally, astrophysicists have believed that these primordial stars, known as Population III stars, were powered by nuclear fusion and contained minimal to no heavy elements—since those elements had not yet been synthesized in the early universe.

An alternative hypothesis was introduced in 2008 by Freese and her colleagues, proposing that the first stars may have been fueled by dark matter instead. Unlike ordinary matter, dark matter does not interact with electromagnetic forces, making it undetectable through direct observation. Its presence is inferred solely through its gravitational effects, and its exact composition remains unknown.

The Role of Dark Matter in Star Formation

According to this hypothesis, dark stars could have emerged from the gravitational collapse of hydrogen and helium clouds in the early universe. If dark matter particles are their own antiparticles, as some theories suggest, then collisions between these particles within the collapsing clouds would have led to self-annihilation. This process would have produced a cascade of particle decay, releasing photons, electron-positron pairs, and neutrinos. While neutrinos would have escaped largely unimpeded, the remaining particles would have transferred energy to the surrounding hydrogen and helium, effectively heating the clouds and enabling sustained growth of the star.

Where Did Dark Stars Form?

These dark stars would have formed in dense regions of dark matter known as “minihaloes,” which existed around 200 million years after the big bang. These protogalaxies contained high concentrations of dark matter, creating ideal conditions for the formation of dark stars. Freese suggests that because of these specific conditions, such stars could only have emerged in the universe’s earliest epochs.

Their Unusual Characteristics

Unlike conventional stars, which emit high-energy radiation due to nuclear fusion, dark stars would have remained relatively cool. This characteristic would have allowed them to continuously accumulate mass over extended periods, potentially growing to extraordinary sizes.

“If you were to observe one, it might resemble the sun in terms of surface temperature,” Freese explains, “but it would be a billion times more luminous—comparable to an entire galaxy of normal stars.”

The Fate of Dark Stars

As these massive dark stars reached the end of their lifespan, they would have eventually collapsed, giving rise to enormous black holes. Ilie suggests that this process could explain the existence of some of the early supermassive black holes that have been observed, which appear to have grown too large, too quickly, to have originated from conventional Population III stars.

Searching for More Evidence

In an effort to identify dark stars, Freese, Ilie, and Jillian Paulin (a former undergraduate student of Ilie’s) analyzed JWST’s catalog of objects from the early universe, nearly 14 billion years ago. Their search yielded nine potential candidates with sufficient electromagnetic emission data for study. Among them, three exhibited characteristics consistent with theoretical predictions for dark stars. These objects showed high redshifts, indicating that their emitted light had been stretched to longer wavelengths—a hallmark of extremely distant cosmic entities. Furthermore, their emissions suggested they originated from a single, concentrated source, rather than from an entire galaxy.

Challenges in Confirming Dark Stars

At present, the researchers possess only limited observations of these objects, making definitive conclusions difficult. A critical indicator of a dark star’s presence would be the detection of a specific absorption feature in its electromagnetic spectrum, caused by a distinct helium isotope. This feature should be exclusive to dark stars and absent in regular galaxies. However, confirming this would require prolonged observation of each candidate—an impractical endeavor given the demand for JWST’s resources across numerous astrophysical investigations.

Despite these limitations, preliminary estimates suggest that if the observed objects are indeed dark stars, two could be nearly a million times the mass of the sun, while the third might be approximately 500,000 times as massive.

The Future of Dark Star Research

To streamline the search for additional candidates, the research team has begun developing automated methods for identifying dark stars. Paulin believes that many more potential examples may exist, waiting to be discovered.

The potential verification of dark stars excites many in the scientific community. Pearl Sandick, a theoretical particle physicist at the University of Utah who was not involved in the study, describes the prospect of directly observing a dark star as “unprecedented.” She also notes that other avenues exist for detecting dark stars, such as analyzing their potential influence on the cosmic microwave background—the faint radiation left over from the early universe.

What This Could Mean for Science

A confirmed discovery of dark stars would not only reshape our understanding of stellar formation but could also provide direct evidence of dark matter interactions. Such an observation, Sandick suggests, would represent a major breakthrough in the quest to understand the nature of dark matter itself.

Furthermore, understanding dark stars could have implications beyond astrophysics. If dark matter annihilation plays a fundamental role in powering these stars, similar processes may still be occurring in regions where dark matter density remains high. This could open new avenues for research into dark matter detection and even influence our comprehension of cosmic evolution.

The Search Continues

Future missions and telescopes may provide additional data to help settle the debate. Advancements in observational techniques, improved computational simulations, and enhanced theoretical modeling could bring scientists closer to confirming or refuting the existence of dark stars. The pursuit of these mysterious celestial bodies continues to inspire researchers, pushing the boundaries of human knowledge about the cosmos.

If JWST manages to conclusively detect a dark star, it would not only confirm a long-standing hypothesis but also redefine what is known about the first stellar structures in the universe. Such a discovery would shed light on the nature of dark matter itself—one of the most perplexing mysteries in modern physics.